Abstract

Introduction: Nutrition plays an influential role in Parkinson's disease. This study aims to assess nutritional obstacles, foods that impact symptoms, dietary guidelines, and consumption of dairy and organic foods in those with Parkinson's disease.

Study design: We performed a multi-site qualitative study evaluating people's nutritional habits with Parkinson's disease.

Methods: Five focus groups were conducted in the United States (n=66); 36 individuals with a diagnosis of Parkinson's disease in various stages participated, as well as 30 caregivers. Data were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed for common themes.

Results: Participants reported some foods that improve symptoms or make them worse. They discussed challenges to cooking and eating. They also reported that physicians provide them with limited information regarding nutrition and diet. There is a disparity between rural and urban people with Parkinson's concerning the consumption of organic food.

Conclusions: People with Parkinson's desire more nutritional information. It empowers them to feel more in control of their disease. More research should be conducted on the effects of nutritional intake and behaviors on Parkinson's disease symptomatology.

Introduction

The gut microbiome influences Parkinson's disease development, progression, and treatment through the gut–brain axis. Research demonstrates that the gut microbiome impacts everything from disease mechanism1 to symptoms such as gait difficulty.2

Nutrition is one of the major factors that influences the gut microbiome.3 Ingested food is digested by gut microbes into metabolites, including neurotransmitters.4 These microbial metabolites circulate systemically and impact every organ system including the brain.5 These metabolites may increase or decrease neuroinflammation depending upon the quality of the diet.6 Pesticides in food may also impact the gut microbiome as these chemicals have been shown to kill some gut microbes.7

Further, some specific foods have been shown to impact Parkinson's in animal models or human epidemiological studies.8 For example, anthocyanins from berries have been shown to be protective, whereas dairy has been shown to be detrimental. However, nutrition is often not addressed in people with Parkinson's disease.

We conducted focus groups among people with Parkinson's and their caregivers to determine what sort of nutritional information was reaching people with Parkinson's disease. This study's goals were to (1) discover whether specific foods (such as dairy) are being consumed in the Parkinson's disease population studied; (2) examine whether people with Parkinson's disease notice that their diet is impacting their symptoms; (3) explore whether organic foods are being consumed in the Parkinson's disease population studied; (4) describe nutritional challenges for people with Parkinson's disease; (5) assess the satisfaction with the dietary guidelines for people with Parkinson's disease.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the National University of Natural Medicine Institutional Review Board. The article was written using JARS-Qual guidelines for qualitative studies.

Research Team and Reflexivity

Focus groups were conducted by ES and HZ (ES asked questions and facilitated the groups while HZ took notes.) ES has a Master's in Clinical Research and a Master's in Nutrition and was a student at the time of the study; HZ has a PhD and was ES's research mentor. Both are female. While HZ has extensive qualitative research experience and training, this was ES's first research study. ES's status as a student was reported to the participants; however, no other characteristics of the research team were conveyed.

Study Design

This study was designed using grounded theory. Specifically, the study was based on the knowledge that the microbiome was involved in Parkinson's disease and that certain foods have been associated with slower or faster disease progression. The theory was that patients were not aware of this research.

Recruitment

Recruitment was carried out by e-mail outreach to Parkinson's disease support groups in Oregon, Ohio, and Washington. Support groups were preferred in this study as this included a group of individuals who have met prior and can provide a comfortable, non-judgmental environment. The investigators had no prior relationship with the people with Parkinson's. Participants knew that their support group was assisting with a research study but did not know anything about the research team. The study team reached out to support group leaders who then asked their groups if they would like to participate. If the group decided that they wanted to participate, then a time was determined for the investigators to meet with the group face-to-face.

Participants

Inclusion criteria for the study included individuals with a self-reported diagnosis of Parkinson's disease or a caregiver, older than 18 years of age, able to write to complete survey or have a caregiver present who can do so, able to speak, read, and write in English or have a translator/caregiver present, and must be able to be present at the focus group to engage in conversations and questions. Exclusion criteria included being unable to attend the focus group. Focus groups were conducted in Oregon (three locations), Washington (one location), and Ohio (one location) (Table 1).

Table 1: Locations of Parkinson's support groups used in study.

| Organization and location | Outreach | Number of total people present | Duration of focus group | Dominant speaker |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Springs at Tanasbourne Parkinson's Disease Support Group; Tanasbourne, OR | 15 | 1:21 | P:3 | |

| Parkinson's Disease Support Group; Cincinnati, OH | 10 | 1:34 | P:1 | |

| Parkinson's Disease Support Group; Beaverton, OR | 8 | 1:01 | P:1 | |

| Willamette View Parkinson's Disease Support Group; Milwaukie, OR | 13 | 0:55 | P:2 | |

| Hoquiam Parkinson's Disease Support Group; Aberdeen, WA | 20 | 0:40 | P:2 |

Informed Consent and Focus Group Setting

Groups met once between April 2018 and September 2018. Before commencing each focus group, an information sheet was distributed and read aloud, and participant questions were answered by the focus group facilitator. All participants consented to audio-recording of the focus group section and confidential participation in the focus group. Focus groups were audio-recorded, and field notes were taken to clarify any garbled speech. To help preserve confidentiality, quantitative data were not coded in a way that it could be paired with qualitative data/voice recordings. Focus group questions are listed in Table 2.

Table 2: Questions and prompts used for focus groups.

| Preparing food |

|

| Satisfaction with dietary guidelines |

|

| Foods that may impact symptoms |

|

Setting and Focus Groups

Participants met in community centers where their support groups typically met. Occasionally, there was a support group leader who did not have Parkinson's present. Data were obtained through open-ended focus group discussions with an average duration of 1 hour. Each focus group was held in a private room (usually at a community center) to support confidentiality and limit distractions. Focus groups were semi-structured, beginning with an open-ended question to encourage participants to describe their own experiences. As the focus group progressed, the interviewer asked specific questions and clarifying questions as needed; an overview of questions is outlined in Table 1. The investigators had an interview guide with a list of questions and prompts to stimulate discussion. No repeat interviews or focus groups were conducted. To maintain confidentiality, participants were instructed not to identify themselves or others by name.

Data Collection

To facilitate confidentiality in the reporting of comments among participants during the focus groups, each participant is referred to by a unique, non-identifying study ID; P: participant with Parkinson's disease, the letter following P is the location of the focus group, and CG: caregiver (e.g., PT1=person with Parkinson's number 1 from Tanasbourne focus group).

After the focus group was conducted, a demographic survey was administered (Table 3). Participants either wrote down an answer or checked a box indicating the correct answer to answer the questions.

Table 3: Demographic data for all study participants who completed the survey (n=25).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 19 (53%) |

| Female | 6 (17%) |

| Age (years, mean±SD) | 74±7.49 |

| Length of diagnosis (mean±SD) | 7.66±8.09 |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 22 (88%) |

| Native Hawaiian | 1 (4%) |

| Japanese | 1 (4%) |

| Latin American | 1 (4%) |

| Annual income | |

| Between $40 and $60,000 | 5 (20%) |

| Between $60 and $80,000 | 4 (16%) |

| Between $20 and $40,000 | 3 (12%) |

| Between $80 and $100,000 | 1 (4%) |

| Between $100 and $150,000 | 1 (4%) |

| More than $150,000 | 1 (4%) |

| Less than $20,000 | 0 (0%) |

| Mean±SD | $74,953±50,771.85 |

| Did not answer | 15 |

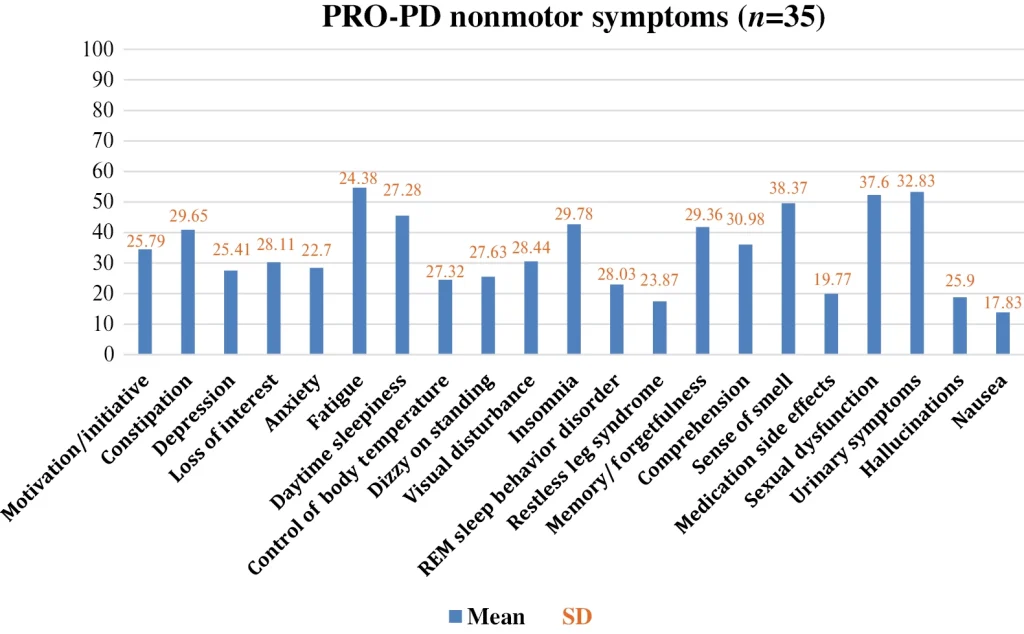

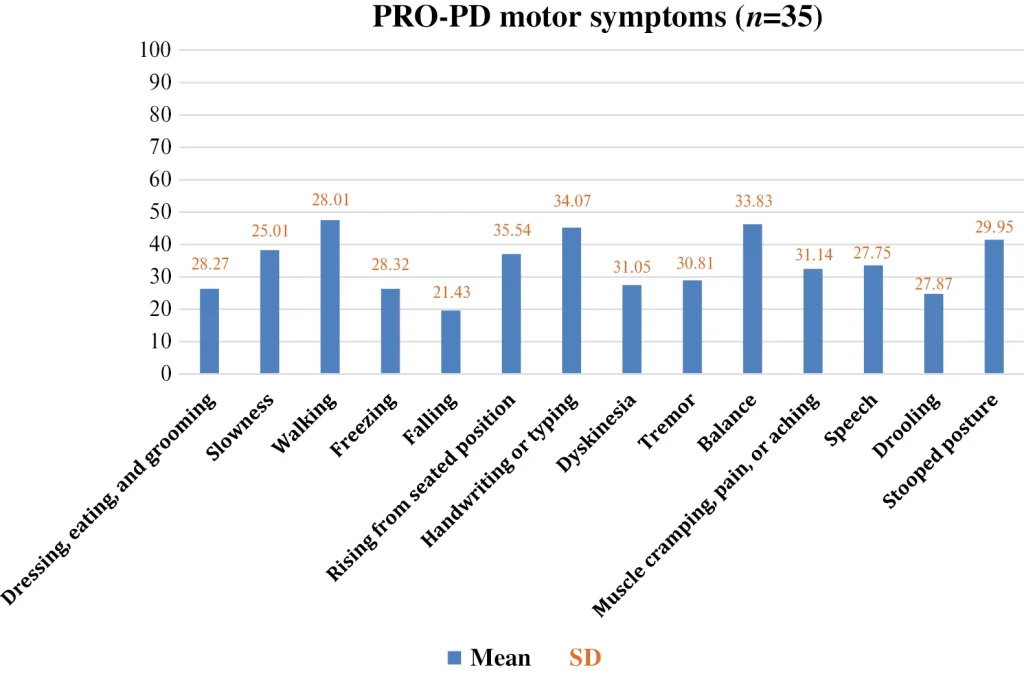

Following the demographics surveys, participants completed a “patient-reported outcomes in Parkinson's disease (PRO-PD)” to assess Parkinson's disease severity, which measures symptoms associated with Parkinson's disease such as gait disturbances, tremor, dyskinesia, and other symptoms (Figures 1 and 2).

Data Analysis

Each focus group was transcribed verbatim by the interviewer (ES). Once all focus groups were completed, all transcripts were read several times open-mindedly, and transcripts were compared to the audio recordings to obtain an overall impression. ES and HZ coded the data using the software Dedoose (SocioCultural Research Consultants, CA, USA). Themes were identified in advance. Exact words and sentences that captured themes were identified. These sections included words, sentences, several sentences, and paragraphs. Quotes were taken directly from subjects that best portrayed the code and answered the aims of the study.

Each researcher analyzed the data independently to identify aspects of the participant's experience. Once each researcher finished coding within Dedoose, the researchers could compare codes and examine the similarities and differences selected. The differences in coding were handled by discussing appropriately until a conclusion was met. Participants were not involved in thematic analysis or feedback. Quotations were identified by participant number.

Demographic and PRO-PD survey information was entered into a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database. This information input was completed on password-protected computers at Helfgott Research Institute, only accessible by study staff. Participants were only identifiable by their unique study numbers assigned by REDCap.

Results

Consent, Demographics, and Pro-Pd Survey Completion and Response Rates

Out of 66 total people, 36 participants had a self-reported diagnosis of Parkinson's disease, and 30 people were caregivers. Out of the 36 participants with Parkinson's disease, 25 participants completed the demographic section of the survey. Out of the 25 participants, 19 were males, and 6 were females. One male participant refused to participate after the first question because he only wanted to talk about alcohol consumption and Parkinson's disease.

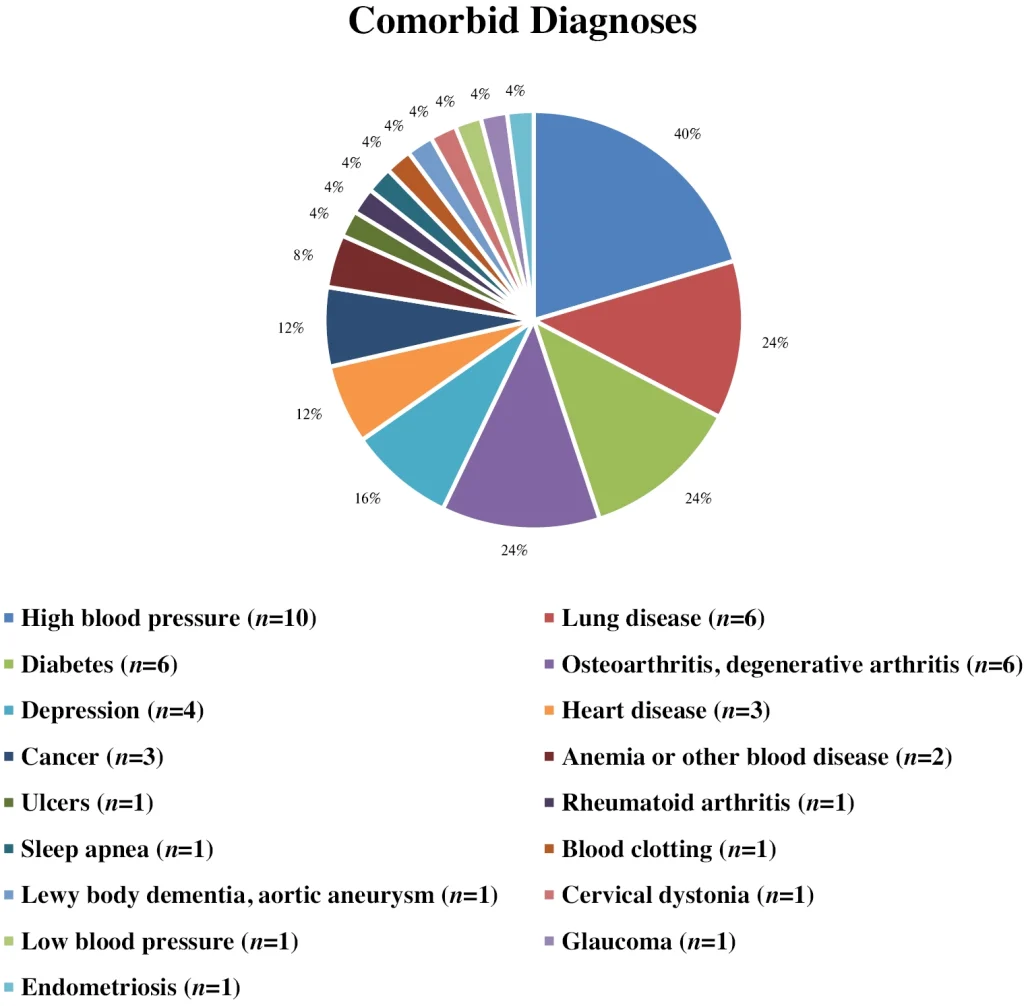

Table 1 depicts the demographic information collected (Figure 2 includes comorbid diagnoses). The mean age was 74±7.49 years, the average length of diagnosis was 7.66±8.09 years, and the most represented race was White participants. The most common income group was $40–$60,000. Complete demographics can be found in Table 3.

Pro-Pd Survey

The results from the 35 participants who completed the PRO-PD survey were divided into motor symptoms and nonmotor symptoms, described in Figures 1 and 2. The most severe symptoms that participants experienced in this study included having trouble walking, handwriting or typing, balance, and stooped posture, all with a mean above 40 (Figure 1). The most severe nonmotor symptoms experienced by the participants in this study were constipation, fatigue, daytime sleepiness, insomnia, memory/forgetfulness, sense of smell, sexual dysfunction, and urinary symptoms, all with a mean above 40 (Figure 3).

Key Themes

Themes, subthemes, and quotes from each focus group are portrayed in Tables 4–6. Themes identified include foods that impact symptoms, organic food consumption, dexterity when preparing or eating food, physical weakness, and nutrition information availability.

Table 4: Illustrative quotes of participant's view on dairy consumption and organic foods.

| Dairy consumption |

|---|

| PM5: I haven't had dairy for 30 years |

| PB3: My dietician says to load dairy as a dessert, you know, almost anything to get those pounds back on |

| PM6: I haven't taken out the dairy. I still continue to drink regular milk because I'm thinking whole milk is going to put some of the weight back on, but I'm still losing |

| PO3: My doctor recommended ice cream to gain weight |

| PM4: Not a day I go without dairy |

| Organic food consumption |

| PM4: I typically consume organic salad, fruits, and vegetables |

| PB2: We try, we go to the Beaverton farmers market and shop at places that are totally organic |

| CO3: My wife and I heard a talk at the world Parkinson's conference that convinced us that we needed to switch to organic milk, which we have done |

| PT3: I've been trying to buy organic fruits and vegetables and organic milk |

| PO2: We try to eat organic as much as we can |

| PA4: I choose not to buy it because it's more expensive |

| PA3: Who can afford organic on limited income? |

| PB5: I think it's a marketing hype |

| PM3: I think the expense keeps a lot of people especially going all organic |

| Pesticide knowledge |

| PT3: Do you guys feel like your doctors are providing you information on dairy products and pesticides? Group members: no |

| PA2: There is a relationship between pesticides and Parkinson's disease? |

Table 5: Quotes from participants that outline their perceived view on foods that impact symptoms and nutritional issues.

| Foods impacting symptoms |

| Improving symptoms |

| PT2: I have dystonia really bad and I have noticed that magnesium seems to help |

| PO3: Dried fruit, especially prunes helps with constipation |

| PT4: Oatmeal makes me feel better |

| PO5: Alcohol can take the edge off for a bit |

| PT3: I don't know about anyone else, but if you have coffee and you take your Sinemet, it kicks in real fast, in 10–15 minutes I am walking so it's great |

| PB3: Coffee makes me feel better |

| PT2: Something else that I discovered that they were trying to figure out if it was an essential tremor or if I had or Parkinson's—um for another reason because I was so anemic they did a colonoscopy and an endoscopy and where gluten is absorbed—I instead of having villi they were nubbins and so they found that I had celiac disease and that meant no gluten, and so that my body wasn't absorbing the carbidopa levodopa at the same place so after I have gone gluten free for a month or two and then started Sinemet once day I could wash my hair instead of having my fingers pause, Interviewer: So you did see a difference in food and diet? PT2: Yes, and I tell people that because I don't think many doctors, nobody even suggested it to me |

| Making symptoms worse |

| PB4: Protein and alcohol makes my symptoms worse |

| CGO1: The only thing I can recall is a lot of Friday nights, we go out for ice cream, and a couple hours later you had a really bad episode |

| CGO3: Well wine I guess if you consider it a food group, um when he drinks—wine especially, if he's tired his speech slurs and that just started happening since he had Parkinson's |

| PO3: A doctor told me I was sensitive to gluten, but I have not cut it out |

| PB2: I might say that dairy is possibly an issue |

| CGM3: She lives on milkshakes. But she was also experiencing some pretty serious gastrointestinal issues and smoothies and milkshakes didn't trigger those problems where some of the other foods did |

| PT5: Sugar makes my symptoms worse |

| Cannot tell |

| PO3: I've never been able to see a cause-and-effect relationship in anything I've done |

| Biggest nutritional issues |

| PT2: Taking medications with food, especially with protein—it becomes overwhelming |

| PO4: Basically, I really couldn't find a whole lot of help for nutrition |

Table 6: Participants quotes that illustrate barriers to food preparation and consumption.

| Themes | Subthemes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Dexterity | ||

| Manipulating utensils | PO1: I find that cutting things up and picking up with a fork is often more trouble than I'm comfortable with | |

| CGB1: He has trouble with manipulating his food or, at the time, his silverware and to try to cut meat, it's very difficult for him | ||

| Manually lifting food to mouth | PO2: Manually lifting food to mouth, that is described as a difficult one for meCGB2: … and then with his tremors he sometimes has difficulty getting the food to his mouth | |

| Packaging | PO3: Yeah, so getting the “inner-selfing” package of cereals can be very difficult | |

| PO4: Trying to get medication tops off is difficult, especially if you have a tremor or you are having trouble with arthritis kind of situation related to your disease | ||

| PO2: I was with my grandbabies today and I had brought them little backs of fish crackers and my 18-month-old, she's like Mimsey, can you open that? And I'm like, I don't think I can open it. You know, I just could not get it open | ||

| Difficulty with cutting food | PO1: I don't have the tremor part of Parkinson's—mine is all gate issues. Um, I do go into pretty severe offs though. And when I do like if it's something like a pork chop or whatever, my husband will cut that up for me because I'll have trouble doing that | |

| PA1: Cutting up food into smaller pieces is difficult | ||

| PO3: And my sister frequently makes pork chops and cutting around the bone just doesn't work. So actually, I just pick the thing up and eat it with my hands | ||

| PO4: Getting things cut because my hands are shaking | ||

| Physical weakness | PO2: I'll even take my little “tumbler cup” to a friend's house or whatever because I'm afraid of dropping one of their glasses or spilling on their table or whatever and it's like I just do that now | |

| Fear of dropping items | PO1: I frequently have TV dinners like “Marie Callenders” or something and those can be tricky to get them to the microwave. You have to take them back to the table and open it up and stir it around and then put it back—that can be pretty tricky walking into our dining room with my leg gait being sometimes the problem, you know getting along. I'm always afraid I'm going to drop it on the floor | |

| Lifting pans | PO1: Picking up a pan—kind of a heavy like a big fry pan and pouring stuff out of it. I have trouble with that. And getting big stuff out of the oven just because I'm afraid I'm going to drop it. I've gotten kind of where I am dropping things now | |

| PA1: Lifting heavy pans out of the cabinet even, I have to have somebody lift a big one if it's something that I'm cooking—something that's bigger than, say my family is coming over and the pans are really heavy for me | ||

| Balance difficulty | CGB3: It's the tremor, it's just the coordination and then he just starts looking at something and then his hand goes from here to there, and then almost like he kind of forgets that the bowl is in hand and it just goes, and I don't know that it because it could be just muscle coordination | |

| PO1: Balance problems—still getting something out of the oven that's hot and big is an issue because some of these—a lot of the containers that I'm pulling out of the oven don't have good handles | ||

| PB2: Sometimes taking and clearing the table and you know, moving things towards the dishwasher—um it's kind of I guess a balance issue and maybe just maybe just a slight freezing situation | ||

| CGM2: Because of his balance issues, I've really asked him to please not go in the kitchen and use knives or use anything that he could hurt himself with because if he falls while he's holding a knife or holding a hot something hot. It's an issue. Kind of said let me do the cooking | ||

| Weight loss | PM2: When you get back to nutrition with Parkinson's that is especially critical because if you've got any of the tremor symptoms or the muscle fighting the motor symptoms. It's taking energy for those muscles whether they're working with each other against each other that takes energy. If you don't get enough energy what happens to the rest of the body? So, you got to get energy into the system to just survive day-to-day. That's where nutrition comes into the play | |

| PA1: Yeah, I have lost weight, but I think it's more muscle tone than anything else | ||

| PB2: I am seeing a dietitian at um Kaiser on the weight loss situation and one of the things that she's got me doing is a very high, caloric drink you know for gaining weight and stuff like that. I had originally been around 195 and I went down to 150 and we're trying to get me to 161 right now | ||

| PM3: It kind of surprised me especially being that Parkinson's—you have to work around, you know, like the whole protein thing with your meals and all that. Um, I was I kind of explained to them that I've been losing a lot of weight and one of the nurses replied, Well, look at the way you're moving around with dyskinesia, you're burning more calories. All the time was kind of the answer to that. And they said oh you're losing all the weight like they told you because look at you. You can't stay still I'm like, well, I realize that, but I need to know how to put everybody having dyskinesia more weight on. So—and I never did find something | ||

| Consuming food | Smell and taste | PA2: I'm losing my sense of smell, which is affecting my taste of foodCGO1: As my wife's care partner, the biggest issue I wrestle with is the fact that her tastes, she has lost her sense of taste and I would love to know some ways in which to enhance either the taste of food for her. Because I do all the cooking, or enhance the mouth feel so that eating is more enjoyable |

| PO2: I hadn't lost my sense of taste by have lost a good deal with my sense of smell. I can still smell when I'm going by “Busken Bakery” out there and stuff like that. I don't smell coffee being made the morning; I only smell when I'm right up close to it | ||

| CG1: You can't taste your food anymore, you can't quite taste your food anymore, or smell it | ||

| PM2: I want to put in one comment that nutrition like you're talking about is tied sometimes to your enjoyment of the food. And if you don't have a sense of smell, you'll find out if your enjoyment of food is entirely different | ||

| PT2: I'm finding food doesn't taste that good anymore | ||

| PM2: I'm finding food taste bad occasionally | ||

| PO3: But for me. I just food sometimes just doesn't taste or sound good to me | ||

| Swallowing difficulty/increased risk of choking | PT3: Well, I have issues with swallowing recently because when I first wake up in the morning, my mouth is really dry. And you know, I go ahead and make my coffee and I'll grab something like a banana or whatever and chewing, it's like it just feels like my mouth can't produce enough saliva | |

| CGM1: When it comes to nutrition, I think for [name] its swallowing very definitely | ||

| PT1: Okay down here trying to get it to slide down and you have the risk of choking if you can't swallow too | ||

| CGB3: He has a little difficulty swallowing because of the weakness in the throat. And so, they advise it if he's eating anything like nuts to be sure to use something that will smooth it down, like yogurt, and that really helps, and he has trouble cutting food into bite-size pieces |

Dairy Consumption

Although there has been shown to be a negative relationship between dairy consumption and Parkinson's disease, most patients with Parkinson's in this study are still consuming dairy (Table 4). Types of dairy consumed include ice cream, milk, cheese, sour cream, and cream cheese. Not only were participants reporting that they eat dairy daily, but two patients stated that their dietician or doctor recommended a dairy product to gain weight. Although some patients with Parkinson's were aware of the association of dairy with more severe symptoms and had reduced or eliminated dairy from their diet, most patients were still consuming dairy. Also, at least one person knew of the relationship between dairy and Parkinson's disease in each of the Beaverton, Milwaukie, Tanasbourne, and Ohio focus groups. However, in Aberdeen, no one knew of the association, and therefore, everyone was consuming dairy. See Table 4 for direct quotations.

Organic Food Consumption And Pesticide Knowledge

Pesticide exposure has been looked at as an increased risk factor for Parkinson's disease.

In Aberdeen, no one knew of the relationship between pesticide exposure and Parkinson's disease and compared to other groups, had the most discussion around not buying organic products due to financial concern (Table 4). In the other four focus groups, some individuals were not sure if they consumed organic food, but most individuals reported having been trying to purchase more organic products. One focus group reported to have not been provided with any information regarding pesticides, which led to many voiced frustrations.

Foods Impacting Symptoms

Some participants voiced that they had a difficult time finding a cause-and-effect correlation between foods consumed and symptoms. However, some foods that were brought up that made symptoms better included coffee, dried fruit for constipation, alcohol, products with magnesium, and oatmeal. Foods that were brought up that made symptoms worse in the patients with Parkinson's in this study include protein, whey, casein, alcohol, dairy, gluten, wine, sugar, and high-sodium foods. Milkshakes fell into both categories. One participant felt better with milkshakes, and other participants noticed their symptoms getting worse with milkshakes. See Table 5 for quotations from participants.

Nutritional Issues And Obstacles

Some nutritional issues that were brought up were overall lack of nutritional advice and medication regime. Food preparation and consumption were commonly discussed and participants voiced frustration around manipulating utensils and holding silverware providing difficulty from symptoms of Parkinson's (Table 6). This in return provided difficulty with lifting food to the mouth. Multiple participants discussed frustration with having tremors and dropping food in the process. Opening packaging was not a specific aim of the study, but participants expressed obstacles trying to open packaging and medication tops because of weakness and tremor symptoms.

Multiple participants voiced concern around weight loss, as well as strategies they are doing now to gain weight and how important nutrition is. There was discussion in the groups about how to keep weight on. Smell and taste were concerns among those with Parkinson's disease. Caregivers are trying to cook foods that make food more enjoyable but sometimes feel at a loss.

Dietary Guidelines

Participants across all groups advocated for an increase in nutrition advice from their providers. When participants were asked if they were satisfied with the dietary guidelines from their providers, all the participants responded with “no.” One participant verbalized that the importance of diet was never emphasized in their care. And because of that, they are not motivated to look more into the literature regarding nutrition and Parkinson's. Participants recognize that nutrition is important and believe that it should be part of the medical system but feel like there is conflicting advice on what to eat. Nutrition recommendations that participants desire include (1) more education, (2) more research, (3) diet and medication, (4) food and symptom severity and progression, (5) diet preparation and consumption, (6) physicians more aware and mindful of nutrition, and informing their patients, and (7) referrals for nutrition.

Medication Regime

Participants stated that timing and eating around medications is challenging and overwhelming. Some participants voiced that they had never been told anything around certain foods and medication. This led to multiple discussions within each focus group on strategies and tips that others have learned regarding diet and medication timing for Parkinson's.

Discussion

This study explored nutritional obstacles present in those with Parkinson's disease, dietary guidelines, foods that impact symptoms, and the impact of consuming dairy as well as organic food products.

Dairy Consumption

Dairy consumption has been shown to increase the risk of Parkinson's disease9 and lead to the progression of disease.10 However, only three prospective studies have examined dairy consumption and Parkinson's disease; a meta-analysis of these studies has shown statistically significant results with a higher consumption of dairy and milk and an increase in Parkinson's disease for both men and women.11 With the association, we were surprised in our study when a majority of people said they were still consuming dairy consistently despite knowing this information. The most common dairy products consumed were cheese, milk, and ice cream. We were equally surprised when some participants stated that their dieticians and doctors have recommended consuming dairy to increase weight. Whether or not physicians have knowledge regarding the association is unknown. Only one rural town was included in this study, Aberdeen, WA. All participants and caregivers in Aberdeen were unaware of the possible relationship between dairy and Parkinson's; in contrast, more participants in the other focus groups were aware of potential issues with dairy based on speakers at their focus groups, but most continued to consume dairy.

Organic Food Consumption And Pesticide Knowledge

Pesticide exposure has been shown to be associated with Parkinson's disease,12–14 and diet is one of the primary pathways of being exposed to pesticides. Organic foods may have less pesticide residue15 and more antioxidants16 as well as more omega-3 fatty acids.17 We found that participants in the rural town, Aberdeen, were unaware of the relationship between pesticide exposure and Parkinson's disease and chose not to purchase organic food because of high cost. Participants in other focus groups were aware of the relationship between pesticides and Parkinson's disease and chose to purchase organic food if possible (when access and finance permit).

A study examining the perception of food systems in large metropolitan cities versus rural communities highlighted a divide in consumption habits. Individuals in larger metropolitan cities purchased and consumed more organic foods and frequented more farmers markets, compared to individuals living in rural communities who rarely or never purchased or consumed organic foods.18 This study suggests that more education regarding organic foods needs to be made available, especially in rural communities. The focus group in Tanasbourne stated that they have not been provided any information on pesticides from their providers, and pesticides were seldom talked about in the Ohio, Milwaukie, and the Beaverton focus groups.

Foods Impacting Symptoms

Limited research has been done examining foods that may impact symptoms in those with Parkinson's disease. Caffeine may improve symptoms such as bradykinesia and other parkinsonian motor symptoms,19 black and green tea might delay the onset of motor symptoms,20 and a gluten-free diet may improve symptoms such as dystonia.21 A couple of participants noted that coffee made their symptoms of walking better, which aligns with the previous study. Some foods were discussed that improved or worsened participants' Parkinson's symptoms. A gluten-free diet provided symptom relief in one participant for her tremors. Foods reported to make participants' symptoms worse were dairy, protein, alcohol, sugar, and high-sodium foods. Several participants stated that they have not been able to determine a cause-and-effect correlation for nutrition or remained silent for this part of questioning.

Nutritional Obstacles

Motor symptoms and nonmotor symptoms in those with Parkinson's disease may impact food preparation and consumption. Participants voiced multiple frustrations regarding the difficulty with manipulating utensils, manually lifting the food to the mouth, frustration around packaging and medication tops and difficulty with cutting food. In addition, physical weakness, weight loss and balance difficulties, loss of smell and taste, and difficulty swallowing allowed for problems around consumption of food.

There were multiple discussions around embarrassment and loss of independence. A study examining attitudes about Parkinson's disease found a common theme from their focus groups showing that individuals had a fear of losing independence and becoming a burden on loved ones, which seemed present in our study.22 These difficulties led to conversations in the focus group on specific strategies that one may use to overcome these frustrations. Finding out what obstacles patients with Parkinson's disease are experiencing could help aid in the design of recommendations and recipes to accommodate these challenges.

Dietary Guidelines And Recommendations

The most prevalent issue discussed in each of the focus groups was lack of nutrition information available to them. We were surprised to see that not all of the participants in this study were given nutrition advice from their providers or even a referral to speak with a nutrition professional regarding diet and nutrition. Patients with Parkinson's disease desire more nutrition guidance because there is confusion and conflicting advice. Our data show that patients want their providers to provide more dietary guidelines and are not satisfied with the current guidelines.

Medication Regime

Several individuals with Parkinson's disease in the focus group voiced concern around being told that they should not eat protein within several hours of taking medication. Sometimes they skipped medication doses if they had eaten protein because they feared what would happen if they took the medication. This is not uncommon in people with Parkinson's disease. Common medication errors in those with Parkinson's disease can involve late, extra, or missed doses. In return, these errors can decrease medication effectiveness as well as the quality of life of individuals with Parkinson's disease.23 In this study, participants shared that timing medication and protein consumption could be overwhelming. This topic should be addressed with effective communication and other tactics, so health professionals can minimize the confusion among people with Parkinson's disease.

Limitations

Our methodological approach combines patient-reported outcomes and qualitative methods to provide a human-centered exploration of the dietary needs of people with Parkinson's disease. There are, however, limitations to our approach and findings. Interviewees in our sample were not from particularly industrialized agricultural regions, likely underrepresenting those with environmental or workplace exposures. People who choose to participate in focus groups may be more actively engaged in their healthcare or more vocal about their opinions and experiences than those who do not participate. Some participants may have dominated discussions while others remained quiet. The presence of more vocal members could have influenced others' willingness to share contradicting views.

Conclusion

Good nutrition is essential to health and may help with management of symptoms as well as disease progression in people with Parkinson's disease.24 Thus, further research is needed on the relationship between nutrition and Parkinson's disease. Moreover, disseminating this research to people with Parkinson's, their caregivers, and their medical providers is essential. Further research is warranted to address nutritional obstacles for those with Parkinson's disease. People with Parkinson's in this study desired dietary guidelines so that they know the potential for different foods to impact symptoms, how to schedule protein consumption which may interact with medication, and which foods, if any, should be consumed only if organic.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

HZ and ES: conceptualization; ES and CF: data curation; ES and HZ: data analysis; AT, LM, and CM: writing and editing.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health AT008924.

References

- Mulak A, Bonaz B. Brain-gut-microbiota axis in Parkinson's disease. World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2015;21(37):10609–20. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i37.10609.

- Scheperjans F, Aho V, Pereira PAB, et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson's disease and clinical phenotype. Mov Disord. 2015;30(3):350–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.26069.

- Kurilshikov A, Medina-Gomez C, Bacigalupe R, et al. Large-scale association analyses identify host factors influencing human gut microbiome composition. Nat Genet. 2021;53(2):156–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-020-00763-1.

- Zhang P. Influence of foods and nutrition on the gut microbiome and implications for intestinal health. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(17):9588. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23179588.

- Gao K, Mu C-L, Farzi A, Zhu WY. Tryptophan metabolism: a link between the gut microbiota and brain. Adv Nutr. 2020;11(3):709–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmz127.

- Malesza IJ, Malesza M, Walkowiak J, et al. High-fat, Western-style diet, systemic inflammation, and gut microbiota: a narrative review. Cells. 2021;10(11):3164. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10113164.

- Kulcsarova K, Bang C, Berg D, Schaeffer E. Pesticides and the microbiome-gut-brain axis: convergent pathways in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. J Park Dis. 2023;13(7):1079–106. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-230206.

- Bianchi VE, Rizzi L, Somaa F. The role of nutrition on Parkinson's disease: a systematic review. Nutr Neurosci. 2023;26(7):605–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.2022.2073107.

- Chen H, Zhang SM, Hernán MA, et al. Diet and Parkinson's disease: a potential role of dairy products in men. Ann Neurol. 2002;52(6):793–801. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.10381.

- Mischley LK, Lau RC, Bennett RD. Role of diet and nutritional supplements in Parkinson's disease progression. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:6405278. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/6405278.

- Chen H, O'Reilly E, McCullough ML, et al. Dairy products and risk of Parkinson's disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(9):998–1006. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwk089.

- Smith-Spangler C, Brandeau ML, Hunter GE, et al. Are organic foods safer or healthier than conventional alternatives? A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(5):348–66. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-157-5-201209040-00007.

- Ascherio A, Chen H, Weisskopf MG, et al. Pesticide exposure and risk for Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2006;60(2):197–203. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.20904.

- Firestone JA, Smith-Weller T, Franklin G, et al. Pesticides and risk of Parkinson disease: a population-based case-control study. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(1):91–5. https://doi/org/10.1001/archneur.62.1.91.

- Vigar V, Myers S, Oliver C, Arellano J, Robinson S, Leifert C. A systematic review of organic versus conventional food consumption: is there a measurable benefit on human health? Nutrients. 2019;12(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12010007.

- Barański M, Rempelos L, Iversen PO, Leifert C. Effects of organic food consumption on human health; the jury is still out! Food Nutr Res. 2017;61(1):1287333. https://doi.org/10.1080/16546628.2017.1287333.

- Mie A, Andersen HR, Gunnarsson S, et al. Human health implications of organic food and organic agriculture: a comprehensive review. Environ Health. 2017;16(1):111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-017-0315-4.

- Bonnell KJ, Hargiss CLM, Norland JE. Understanding how large metropolitan/inner city, urban cluster, and rural students perceive food systems. Urban Agric Reg Food Syst. 2018;3(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.2134/urbanag2017.06.0001.

- Palacios N, Gao X, McCullough ML, et al. Caffeine and risk of Parkinson disease in a large cohort of men and women. Mov Disord Off J Mov Disord Soc. 2012;27(10):1276–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.25076.

- Seidl SE, Santiago JA, Bilyk H, Potashkin JA. The emerging role of nutrition in Parkinson's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:36. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2014.00036.

- Vinagre-Aragón A, Zis P, Grunewald RA, Hadjivassiliou M. Movement disorders related to gluten sensitivity: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2018;10(8):1034. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10081034.

- Pan S, Stutzbach J, Reichwein S, et al. Knowledge and attitudes about Parkinson's disease among a diverse group of older adults. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2014;29(3):339–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-014-9233-x.

- Buetow S, Henshaw J, Bryant L, O'Sullivan D. Medication timing errors for Parkinson's disease: perspectives held by caregivers and people with Parkinson's in New Zealand. Park Dis. 2010;2010:432983. https://doi.org/10.4061/2010/432983.

- Baroni L, Zuliani C. Ensuring good nutritional status in patients with Parkinson's disease: challenges and solutions. Res Rev Parkinsonism. 2014;4:77–90. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPRLS.S49186.